The crew of the B-24H Heavy Bomber Boojum |

Click Picture for Site Index |

Book now available, click image |

The crew of the B-24H Heavy Bomber Boojum |

Click Picture for Site Index |

Book now available, click image |

|

In the spring of the year 2002, just after the 10th year anniversary of my father’s (Frederick G. Abner, Jr.) death, I read a book by Stephen Ambrose with the appropriate title The Wild Blue. I picked up the book when I saw it displayed in a bookstore thinking that I would read it as a tribute to, and in memory of, my father. It told the story of the 15th Air Force in Italy during World War II, and in particular, detailed the service of Lt. George S. McGovern , a B-24 pilot who flew 35 missions against Nazi Germany during the years 1944 to 1945. He later. of course, became a Senator from South Dakota and the democratic candidate for President of the United States in the 1972 election. McGovern was assigned to the 455th Bomb Group, 741st Squadron. I knew my father was stationed in Italy at that time and decided to research his unit and squadron. This research led me to the 456th Bomb Group Association where, with much help from the members of the association, I was able to gather the information that follows. | |

| |

By coincidence, Michael J. Dancisak, Ph.D at Tulane University, son of George L. Dancisak the flight engineer, and I both posted messages on the 456th Bomb Group Association's web page guestbook requesting information about the crew of the Boojum. This prompted Robert W. Reichard, a bombardier on another plane from the 745th Squadron, to contact the association's historian, Fred H. Riley, on our behalf. Fred subsequently sent both Mic Dancisak and myself the name and email address of the co-pilot of the aircraft, Howard N. Hartman, who is an association member. Much of the information about the crew and the last mission on April 3, 1944 was provided by Mr. Hartman. Together, the three of us researched and compiled the stories, photos, and data presented below. Later on, we were able to contact Hans Halberstadt, the son of Milton H. Halberstadt, the navigator, who provided us with the navigator's log book and additional photographs. At the 2003 456th Bomb Group Reunion in New Orleans, LA, we met Edward L. Dement, top and nose turret gunner, who filled in many of the missing details. Mr. Dement has also written a book about his experiences in the POW camps entitled, Sergeant, for you the War is Over, which I have quoted from extensively below. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Howard Hartman's Pilot Training Experience"I was called in Oct. 1942 and met 500 other cadets for a private train ride to Nashville, TN for classification. Many kinds of tests were given to see what you qualified for. I qualified for pilot, and with those others who made pilot went to Maxwell Field, Montgomery, AL. We were on the honor system and signed papers after a test that we had not given nor received any help. We lived six to a room and we had 15 minutes in the morning for all of us to shave and shower. (It took longer to shower if you turned the water on.) After two months of pre-flight training we were sent to many primary flying schools through out the South." "Most were grass flying fields. I, and some friends I made for the rest of my life, went to Charlstrom Field in Arcadia, FL, East and South of Sarasota. It had been a private flying school before the army took over and we never again had such splendid quarters. It was all white washed and looked like a resort with swimming pools and tennis courts." "We flew Stearman P.T 17's, a by-wing with front and aft cockpits. The instructor sat in the rear seat. The landing wheels were very close together and made the plane subject to a ground loop on landing. Two of these and you were out. We started to solo by 6 hours and had to solo by ten or you were washed out. On arrival they told us to line up and look at the men on each side of you. Then we were told that only one would graduate from Primary Flight school." "We were in Arcadia during March and April. We did 60 flying hours. One of my roommates had ground looped on an auxiliary field and he was standing with his instructor and mine, when I took off for my day after solo flight. My roommate heard my instructor tell his instructor, 'There goes Hartman, he soloed yesterday by the grace of God.' " "Those of us who survived were sent to Basic Flying School in Bainbridge, GA. The town was even smaller than Arcadia, but the locals were super kind to us. We flew a ship we called the Vulteen Vibrator. It was a single engine plane with the instructor in the back seat. This was the first plane that had so much torque that the whirling propeller pulled us to the right on landing. We had to overcome this by crabbing to the left. Early on as I was approaching for a landing on a concrete runway, I was being pulled to the right. My instructor said, 'Hartman, you are to land on the runway, not the grass beside it.' " "After 60 hours of basic flying during May and June of l943, we were put in an open truck convoy to Valdasta, GA, for twin enging training. We flew AT 10's. The instructor sat beside us. By now we could fly quite well and we learned formation flying and much navigation. When we couldn't find our way home, we followed the railroads, got oriented and flew home - flight plan slightly adjusted. My class graduated with our pilots wings on Aug 30, l943. Fifteen of us were sent to Mountain Home, Idaho, just outside of Boise, where we were assigned as co-pilots and met our crew." "After much training in gunnery, bomb dropping (flower bags), and formation flying, we picked up a new B-24 in San Francisco and flew to the East Coast, then to Brazil and across the Atlantic to Africa. We arrived at our Italian base on Feb. 1, 1944." |

|

|

|

|

Flight training took place at Mountain Home and then Muroc between “. . . September 1 and most of November (1943). Then we went to Frisco (San Francisco) to pickup a new B-24. We waited many weeks for that to happen.”*

Enlarge Photo |

“Then we flew it (the B-24) to Palm Springs had an over night plus and saw what there was of the little town. A wealthy man invited us to play on his private 7 hole golf course. Flew to Midland, TX and got caught in a heavy snow storm and stayed there 2 or 3 days, then another stop (Kansas City), and finally to Palm Beach, FL and then to Trinidad. Almost had to ditch as we landed on fumes. Had trouble with the (engine) cowl flaps on the way down and we couldn’t fly very high – had to dodge storms. Then on to Belem, Brazil at the mouth of the Amazon. Then from Natal, Brazil on the coast to Dakar, Africa, then for a stay outside Marrakech, Morocco until Italy in Jan. 1944.”* * As told by Howard N. Hartman |

|

2nd Lt. Milton "Hal" Halberstadt's |

January | 1944 |

Date | Flight Operation |

| Jan. 4 | Hamilton Fld to Palm Springs, Calif. |

| Jan. 6 | Palm Springs to Midland, Texas |

| Jan. 10 | Midland to Memphis, Tenn. |

| Jan. 11 | Memphis to Morrison Fld, Fla. |

| Jan. 14 | Morrison Fld to Waller Fld, Trinidad |

| Jan. 15 | Waller to Belem, Brazil |

| Jan. 16 | Belem to Natal, Brazil |

| Jan. 18 | Natal to Dakar, Africa (now Senegal) |

| Jan. 19 | Dakar to Marrakech, Morrocco |

| Jan. 20 | Marrakech to Telerema, Algeria |

| Jan. 21 | Telerema to Oudna, Tunisia |

February | 1944 |

Date | Flight Operation |

| Feb. 1 | Oudna to Stornara, Italy |

The aircrews and aircraft assembled outside Tunis, Tunisia during late January 1944. From there the 456th Bomb Group flew into the Foggia area of Italy near Cerignola and Stornara on February 1, 1944.

Enlarge Photo |

|

|

The ground crews had arrived in Italy by boat on January 19th and had moved to Cerignola on January 25th. The crewmen lived in tents pitched in between the trees in olive groves adjacent to the airstrip.

|

|

|

Enlarge Photo |

|

Enlarge Photo |

|

Enlarge Photo |

|

|

For a great description of what life was like on the ground see the story by Bob Reichard at the 456th web site.

For more stories by Robert W. Reichard, see his book, One Soldier's Story, edited by David F. Abner, which is a collection of stories of Mr. Reichard's unusual military career. Robert W. Reichard was a Bombardier on a B-24 Liberator flying with the 456th Bomb Group, 745th Squadron during World War II, is a Korean War veteran and member of the Chosin Few, and was a Military Policeman and Paratrooper stationed in Berlin and Augsburg, Germany during the Cold War. Mr. Reichard also served in a number of peacetime military positions and his stories are rich with eye witness detail and insight, which provide a window into the history of those turbulent times. | For information about ordering the book, click here. |

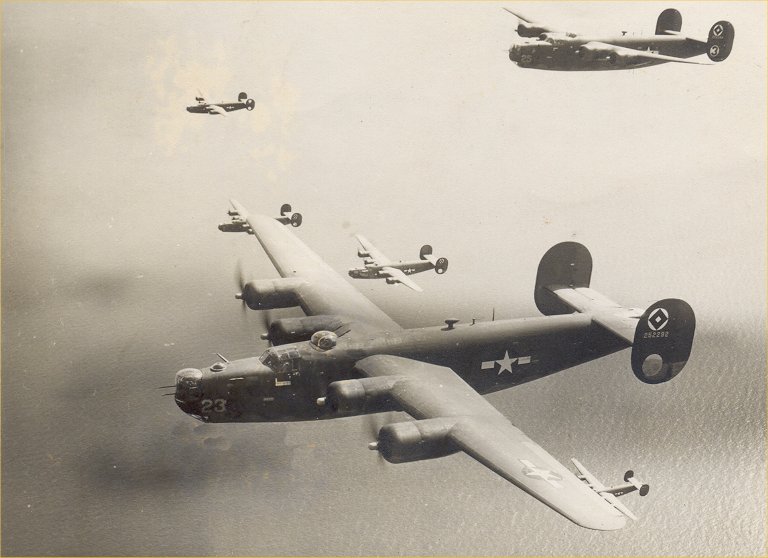

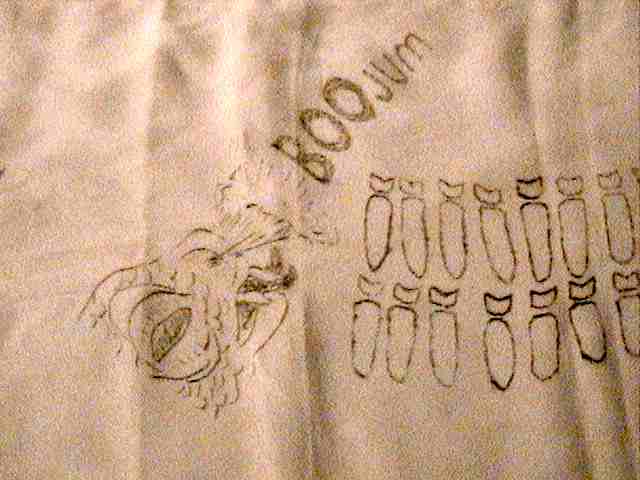

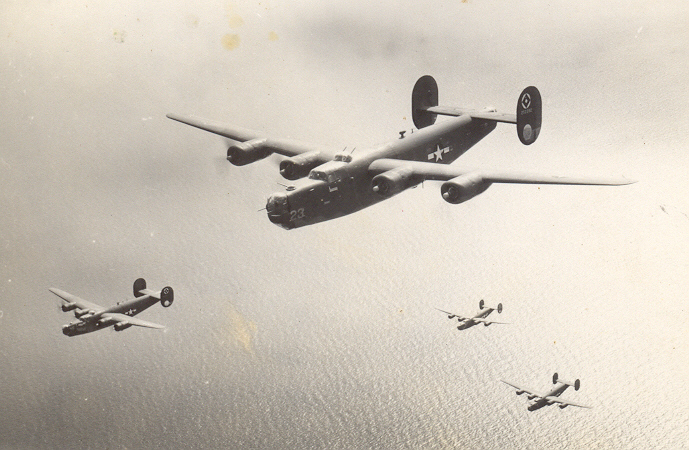

The airplane was a B-24H, tail number 42-52292. The tail number indicates that the plane was built in the Ford factory in Willow Run, Michigan during 1942. The crew named the aircraft Boojum at Milton Halbetstadt's suggestion, from the Lewis Carrol story Hunting of the Snark, and painted a Dragon on the nose. Anyone, in the Carrol story, who looked upon the mythical monster Boojum evaporated, they would "softly and suddenly vanish away."

Courtesy of Michael J. Dancisak |

|

The crew consisted of the following airmen: *

*Fred H. Riley, association historian.**Robert Heaton transfered to flight school prior to the crew deploying to Italy.***Reinaldo Garza was killed in action on March 19, 1944 during group mission #16 to Steyr, Austria while flying on another aircraft, The Paper Doll. He was replaced by Howard Kiefer.****Howard Kiefer was killed in action on June 16, 1944 while flying in the plane Sky Gazer on group mission #69 to Vienna, Austria when the plane was shot down by two ME-109s. |

Frederick G. Abner, Jr. flew 18 missions as a ball turret gunner with the crew of Boojum and as a substitute gunner on other aircraft. The targets of the 456th Bomb Group during that time included army command posts, marshalling yards, railroad bridges, and airdromes in Italy, harbors in Yugoslavia, aircraft factories in Graz, airdromes in Vienna (Bad Voslau) and Steyr (Klagenfurt), Austria, industrial areas in Sofia, Bulgaria, and the main marshalling yard in Budapest, Hungary.

A complete list of missions is availble at the 456th web site.

Also refer to the 456th Bomb Group Calendar for a calendar by month of missions flown by the group, January - April 1944.

|

I remember two incidents in particular that my father related. On one occasion I asked him if he had ever shot down an enemy fighter. He laughed and told the story of how he had shot down some bomb bay doors. During a mission, an aircraft above and slightly in front lost its bomb bay doors. Fighter activity on this mission had been heavy. As the bomb bay doors floated down they lined up together and to Fred in the ball turret, looked like the wings of a fighter. He fired the two 50 caliber machine guns in the ball turret and to the delight of the rest of the crew, scored a direct hit and “kill” on the bomb bay doors.

Another incident that he told often as a war story involved a mission where heavy flak was encountered. (See Mission #10, March 22, 1944 in table below). On that mission, flak hit in the bomb bay causing fuel to stream out of several fuel lines. He reached out over the hole in the bomb bay and stuffed rags into one damaged fuel line, to stop the leak. He was able to stop the leak, but the fuel ran down the inside of his flight suit, burning his left arm and leg. The temperature at 25,000 feet was often below zero and the fuel was so cold that it basically caused frostbite burns.

George Dancisak, the flight engineer, also received burns from the fuel over most of his chest and back working furiously to stop the fuel leaks. Howard Hartman remembers seeing George with his flight suit off, naked from the waist up, covered in aviation fuel. Mic Dancisak remembers that his dad's skin, where he had been burned, bothered him through the rest of his life. The fuel leaks were stopped and the plane made it safely back to base. For some unknown reason, neither George Dancisak or Frederick Abner were awarded the Purple Heart for their wounds.

Missions Flown by the Crew of Boojum

* Crewman Reinaldo C. Garza was killed in action while flying on the airplane "The Paper Doll" which exploded in mid-air after being attached by fighters.

|

Fred was ordered to bail out, along with five other crewmen, during Group Mission #25 on April 3, 1944. The target was the marshalling yards in Budapest, Hungary. Fred said they were hit by flak over Yugoslavia and the pilot ordered the crew to bail out. He was the first to bail out. He was subsequently captured by the Germans and was a POW for 13 months. More on the prison camps later.

| |

“The day we got hit by flak we had just crossed the coast of Yugoslavia, had just gone on oxygen when we were hit in the nose and one engine. We were at just over 10,000 feet and the Germans had moved in ack-ack on railroad cars. We lost altitude immediately and tried to stay aloft by tossing out anything that was loose, the bombs, bomb bay doors, and try to fly back. Hit the Adriatic Sea and still falling. Turned back inland and Lazewski (pilot) ordered everyone to jump. Bonham came up to the flight deck and said Halberstadt (Navigator) was too wounded to jump. George Dancisak went down to the navigation, bombardier station to attend to Halberstadt. Meanwhile, I started jumping the crew. After Abner, Thompson, Fischler, Dement, and Bonham jumped we were quite low and almost steady. I talked with Laszewski and we knew the plane, although not losing much altittude, would not make it to Italy. When I jumped, the plane stopped falling. With my 200 lbs. And gear, that was enough. Lazewski turned about and headed west. I hardly had my chute open when I hit the ground, hid the chute, when the plane flew over my head, headed for Italy, and open waters for sea rescue if necessary. Some of us were taken by truck to a farm house, put in an underground cellar and locked up. I asked for water and the farmer, I’am guessing, took me to a water pump, and when I drank I could see out from under my blindfold. I saw Thompson sitting down. He too was blindfolded and I called out his name to let him know I was there. Wham, no more water. Next day the entire crew was in a prison in Belgrade. Not together but as we used the facilities we saw each other. Never again, until Camp Lucky Strike when Fischler was riding past in a truck and spotted me. Then I learned that all the crew had made it through the war. What a wonderful relief.” |

The crew was not flying in Boojum that day. Instead, they where flying in The Texas Ranger, tail number 42-997849. Below is a direct quote from page 14 of the 456th Bomb Group 1943 – Steed’s Flying Colts – 1945 history book dated April 3, 1944:

“Aircraft No. 177 “The Texas Ranger” , a 745th Squadron plane, manned by the

crew of 1st Lt. Emil S. Laszewski was severely damaged by anti-aircraft. Lt.

Halberstadt the navigator was wounded. When it appeared that the ship would not

likely make it back to the base, six of the crew bailed out over Yugoslavia.

|

Frederick Abner remembered that after he jumped, he dropped toward a farmer's field. He was unable to control the parachute and landed hard on a stone fence hurting his back. Fred walked up to the farmer to ask him for directions to the coast, since reaching the coast would increase the probability of rescue. Just as he was trying to communicate with the farmer, a German patrol arrived and captured him.

|

The following account was part of a story about 2nd Lt. Milton H. Halberstadt, the injured navigator, published in the Plainfield (NJ) Courier-News. The article explains why some of the crew didn’t jump and provides some information about the flight back:

“The flak which caused Lt. Halberstadt’s injury, continued on through the side of the Liberator, short-circuiting the electrical system, and finally hit and exploded in the #2 engine, puncturing the oil line. The only instruments left to navigate the ship were the magnetic compass and the altimeter . . . Sergeant Dancisak, excusing himself from not jumping when ordered, said, ’Someone threw my 'chute straps overboard while we were trying to decrease the plane’s weight. Anyway, if we leave the ship, it means Lt. Halberstadt will have to crash with it. He could never ride a ‘chute in his condition. I’ll stick with the ship, sir." | |||||

| |||||

Sergeant Kiefer also was apologetic about not obeying orders. Explaining

himself he said, ‘The interphone was out when the pilot first told us to jump,

and I thought we might run into some enemy fighters. Someone had to stay and

help out a little.’ Sergeant Dancisak gave first aid to Lt. Halberstadt. ‘The lieutenant kept conscious all the way back. He even gave us a heading that helped us find our way. We still don’ t know how he did it because he lost a lot of blood. I guess he wants to get back and see that kid of his that he’s never seen’ The pilot (Laszewski) said that the trip back seemed long and tedious. ‘We couldn’t seem to get up any air speed and we had a long way to go.’" Halberstatd recovered in a field hospital, although his injuries necessitated the amputation of three fingers. |

|

|

| |

“Monday morning, April 3, 1944 was like the past days, cloudy and overcast. We never dreamed that there was going to be a mission today . . . This was my 25th mission. At 20 years old I was looking forward to the Isle of Capri for rest and relaxation. However, other plans were being made. Briefing for the gunners was held at 5:30 am and we were told that the target for today was the first raid on Budapest, Hungary." "Sick call was not permitted after the mission had been announced. The crew proceeded to a hut where all of us picked up our parachutes and harnesses, flak jackets, and Mae Wests (to be inflated if we entered the water). We waited for transportation to a plane called Texas Ranger." ". . . there was no such thing as a milk run. Every mission was fraught with danger. The first flight into enemy territory frequently was the last. The name of our plane was Boojum. Boojum carried us on many missions. The Texas Ranger that we were to fly this day was a plane that was a month late arriving in Italy and never made a mission in nine starts. Our pilot was chosen to prove that the plane was okay." We had just crossed the coastline of Yugoslavia, climbing to 12,000 feet. At this altitude the crew put on oxygen masks and noticed small bursts of flak ahead. In seconds there was a loud explosion behind the nose turret. The ship seemed to lift a little, and at the same moment, all instruments toppled back to zero. Our pilot tore off his mask and reached up to feather number two engine." "Lucky for us, the 88 millimeter shell did not explode, but the fuse from the 88 caused all the damage. The fuse hit the navigator, . . . bounced off the flak vest, and went to lodge in the oil line of the number 2 engine. The only working instrument we had was a compass mounted high on the windsheild . . . We were losing altitude rapidly and the number two engine could not be feathered. The plane was turned toward the Adriatic Sea. Still falling, our pilot turned back over land. He ordered the crew to throw out any equipment they could." Our engineer waist gunner was summoned by the bombardier to help give first aid to the navigator. I remained in the top turret scanning the sky for enemy fighters, which normally come up to finish a crippled plane falling out of formation. No fighters were seen. With the electrical system gone, the emergency release was used to drop our bomb load. The bomb bay doors did not open and the bombs went through without exploding." "The order over the intercom came for us to leave the plane. The gunners in the back left the plane first. The engineer gunner's parachute fell through the bomb bay so he had no choice but to stay with the injured navigator. The co-pilot pulled on my leg for me to leave the turret. I looked down through the bomb bay doors which were flapping in the breeze. My GI shoes were laying on the flight deck and I remembered to hang them around my neck. I hesitated, fear engulfing my mind, my legs were shaking, harsh wind burned my eyes and battered at my face. The co-pilot gave me a nudge and I left the plane feet first through the bomb bay." ". . .Looking down I saw the ground coming up fast. The last 50 feet was my own undoing. As I came toward the pine trees on the side of the mountain, my chute caught the top of a tree. I fell through the branches, breaking each one. Finally, I landed on the rocks with my knees and face . . . After laying there for a short time, I began to hurt all over. My nose was bleeding and seemed to be all over my face. I then knew it was broken. I tried to stand up and fell back, both knees were feeling either dislocated or broken . . . Feeling under my flight suit, my hand came out bloody. I knew I had ruptured my navel. Both legs and arms were bloody from the broken branches. I landed on the side of a mountain near the city called Mostar, Yugoslavia. I also knew that I was back on earth because I could hear the barking of a dog in the valley." "We bailed out at approximately 9:30 in the morning. It was close to 3:30 in the afternoon before I heard voices. The voices were Germans . . . Two of the young boys picked me up and carried me down the mountainside. At no time was I given first aid. The pain was getting worse. Down in the valley, I was put in a Ford truck . . . They drove for some time until we came to a village where I was left unattended while the soldiers and boys went inside the building. I could hear a lot of loud talking and yelling. Suddently, I was grabbed and pulled from the truck by civilians. They started kicking my back and stomach, punching my face and head. For some reason, my legs were not kicked. I am sure if that had happened I would rather have had a bullet. My pain was so severe I threw up." "With all of the commotion, the guards finally came out, firing their rifles in the air, and everyone disbursed. These soldiers saved my life. I was put back on the truck. We made several stops; each stop was picking up another member of my crew. I heard their voices. Soon six of us were on the truck I was the only one that was hurt. Four other members of the crew were unaccounted for." ". . . We stopped after dark. We were taken off the truck and ordered to a large civilian prison. Each of us met a German major who spoke broken english and who gave orders for us to be taken to the third floor . . . Because of my injury, I was carried to a cell. Two men were assigned to one cell and we were given, for the first time, food and water, which was German black bread, meat, and ersase coffee." ". . . We were awakened at 4:30 am by crying, screaming, and shouting. My cell mate, looking through a small opening of the cell door said that they were carrying, dragging, and pulling young boys and girls down the hall. We thought they were going to be interrogated. That was not the case. A short time later, we heard machine gun fire below our window. The wall below our third floor was the execution wall. These young people were captured partisans that were rounded up the day before." "You can imagine what we were thinking. With no proof that we were airmen it could be just a matter of time and we too could be placed against the wall. I asked my cell mate if he would take off my shoes as my feet and legs were in great pain. The moment he removed my shoes a guard brought in food and water and saw my dog tags in my socks. He removed my tags and took them to the German major. Two guards came, carried me to the German major's office and questioned me. 'Did I know Al Capone the Chicago gangster?' I was asked because my dog tags indicated I was from Chicago. He asked me a few questions about my crew and gave my dog tags back to me. When I was being carried back to the cell, he said that there was no doubt we were airmen. These tags saved the entire crew." " . . .Within a day, our co-pilot was taken away and never seen again . . . After two days confinement, a German medic rendered first aid for my knees. He put my leg between his and with a jerk, plus a scream from me, put my knee back into the socket. Then he went throught the same motion with the other leg. The pain was so severe that I passed out. Two days later I was able to stand but I walked with a limp. Nothing was done for my broken nose except for a rag for cleaning the blood. A salve was put on the many cuts for my arms and legs. My naval was never looked at." |

| ||

In a letter from Milton H. Halberstadt to Howard N. Hartman dated January 17, 1990, Halberstadt writes " . . . the plane we were assigned for this mission in place of our Boojum was hit by the fuse of an 88mm shell over Mostar, Yugoslavia some 46 years ago. After bouncing off of my flak-suit it knocked the electrical system out and went on to lodge in the oil line of the #2 engine which had to be feathered - whew, no wonder my stomach was so sore for a week!" Halberstadt continues, "I must confess that I had a premonition and for the first time in our 10 missions I plotted back-headings for this one." Then Halberstadt sheds some light on why the crew was flying in another airplane, "We were on the Great! Texan's plane, Texas Ranger. I blocked his name a long time ago. He's the one who wore 6-shooters on his hips. He was a month late reporting to Italy (I have never been able to watch Catch 22 - the little I've seen of it reminds me of him). He's the one that had never made a mission in 9 starts, and ol' reliable Jeff (Laszewski) was chosen to prove that the plane was OK and that Tex was not." "I was just writing in my log: '10:05 Mostar, 10,000 feet, climbing' and I can still see the hole in the fuselage just above Bonham and to the right of Keifer, the substitute nose-turret gunner. (Amazing how the brain can at times actually slow-motion the action! )" About his stay in the hospital, Halberstadt writes, "I remember . . . someone holding up my flak-suit as an example of why one should wear a flak-suit. And I remember Col. Steed giving me the Purple Heart the next day and his saying, 'I'm sorry, I knew we shouldn't have been there.' " "I like to think it may have been more profound than that - I married a Hungarian, studied and lived and worked with Hungarians and maybe, just maybe - that bombing Budapest was off-limits for me." | ||

In a letter home to a friend of Howard Hartman's dated May 10, 1944, pilot Lt. Laszewski wrote, ". . . we started off on a raid on Budapest. Things were going along fine till we had crossed the coast of Yugoslavia and about 20 miles or so inland, we received a direct flak hit in our nose of the plane. It seriously injured our navigator but no one else was hurt. The burst however badly crippled our ship. It disabled our entire electrical system and knocked out No. 2 engine. We turned back for home but lost altitude rapidly. We had to fly clear across the Adriatic to do this but Howard and I couldn't see how we could make it without crashing in the sea. So we salvoed our bombs to lighten the load and we turned back inland just off the coast and I told Howard and five others to bail out rather then wait till it was too late."

A member of the ground crew, Bob Perry, who later flew as a turret gunner with Lt. Laszewski and Sgt. Dancisak on the aircraft Reluctant Beaver, wrote in a letter to Michael Dancisak : “Before I was flying with him, Lt. Laszewski bounced the remains of his B-24 along the runway, with the help of your dad (George Dancisak).”

Ironically, it was George Dancisak’s birthday.

Laszewski and Dancisak would never fly in the Boojum again. On April 12, 1944 on group mission #29 to Bad Voslau, Austria, Lieutenant Meyers and his crew were shot down while flying Boojum. To read the statement about the incident from a pilot and co-pilot who saw the plane go down, click here.

Bob Perry in an email related the following about a mission on May 27, 1944 while flying as a nose gunner with Lt. Laszewski and Sgt. Dancisak in the Reluctant Beaver, Aircraft # 42-78239: "Once while scanning to my left, port side of the plane, I saw a cylinder detach from the number one engine (outboard on port side) I don't remember if it was fighter or flak that caused it, but the darn thing just popped straight up and then drifted back as the plane left it. The prop was immediately feathered and then we had turned back to Corsica. We jettisoned about everything that could be detached, and limped in to Ajaccio (Corsica)." Bob Perry also remembers that Lt. Oran R. Key, Jr. was the co-pilot and Jonas A. Leopold, Jr. was a crew member on the Reluctant Beaver.

courtesy of Michael J. Dancisak, |

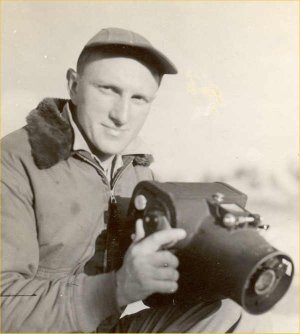

On a mission to Ploesti on May 5, 1944, George Dancisak captured a picture of a B24 that had lost its wing tip and was falling out of control. To view the picture, click here.

Laszewski and Dancisak went on to complete the required number of missions and were eventually rotated back to the states. Michael Dancisak remembers that his "dad said he locked the hatch and walked away without looking back."

Robert W. Reichard, bombardier on the B-24 Phoney Express II, echoed the same type of sentiment on May 8, 1945 when he was informed that the war with Germany was over, "It was as if someone had let the air out of an over-inflated balloon."

A similar testiment can be found at the 456th Bomb Group Association's web site where the motto reads, "We had a job to do. We did that job."

In other emails, Howard N. Hartman writes,"The interrogation center in Frankfort on the Mein River had all 6 (of us). Somehow the Germans had all our names. They even had an article about me from my home town, Shelby Ohio, population 6000, newspaper and knew my father's name. Had a large photo-type book with big numbers on the cover - 456th bomb group. . . I was in Stalag Luft 1 north on the Baltic Sea. The Russians liberated our camp. Held 10,000 men. Your father (Frederick Abner) was in Stalag Luft III with all the enlisted crew. I forgot where Bonham was.”

| |

"When I arrived at Stalag Luft 1, they had recently openned North 1 Compound and our train load of new arrivals (arriving in box cars) were marched through the small town of Barth enroute to the camp about a mile away. The local women shouted at us and hit us with brooms. rakes etc as we marched past them. We were assigned 14 to a room, double bunks. The room had a small cast iron stove in one corner, an oak table that could seat six on two benches, one 40watt light bulb, and double windows which were covered at night by outside shutters. Above the window was an opening about eight inches wide which had a cardboard cover that could be slid open after we were shuttered-in and lights were out. Guards with dogs, patrolled the grounds. We had one sheet, one thin blanket and slept on straw filled mattresses. In the winter we slept in our clothes and an overcoat. It was the coldest winter in years for that area." "Red cross parcels were issued once a week in the beginning. Several of the items were taken for the kitchen. We had a large building that could seat several hundred at a time. We had barley, with bugs, in the morning, a little food the Germans provided, and something from the red cross parcel like Spam. The mess hall burned down shortly after our arrival. Next to the mess hall was a dug out basin to catch water used to fight fires. It was not sufficient (to save the mess hall). After that we got food directly to each POW, but the parcels were giving out and distribution reduced until there was none in the spring of l945." "We had a secret newspaper. The British in compound 1 had gotten radio parts from a guard in one of the towers who had fallen asleep, and they knocked on one of his legs to awaken him and told him he was going to be reported to German Headquarters. He offered a present if they did not report him. The British then had a radio and listened to the BBC once a day. Notes were taken on toilet paper and the Catholic priest carried them in a false watch from compound to compound. Lowell Bennett, an International News Service young reporter who had been shot down while riding with the British on a night raid, expanded the news and published the paper know as POW WOW - Prisoners of War Waiting on Winning." "My bunk mate in the lower bunk, Phillip Melnick, was of Russian Jewish ancestry. He was taken, along with all other Jewish soldiers and put in a barracks by themselves. Story was they were to be executed, but with the end of the war not far away, the orders were not carried out." "The Russian Army liberated us and held us for two weeks while they compiled information on all 10,000 prisoners. We were flown out of Barth airport by the 8th airforce. Then a train ride, with milkshakes three times a day to fatten us up, to Camp Lucky Strilke in France. There were over 50,000 liberated prisoners there. That is where Samuel Fischler jumped down from an open truck when he saw me. It was the first I knew that the crew had survived the war." |

|

|

My father and the other enlisted men were placed in Stalag Luft III. In an email, Edward L. Dement recalls, "I was in the same barracks with your dad for four weeks. In May 1944, your dad and Thompson were moved to the west compound. Fischler and I stayed in the center compound. I saw your dad and Thompson again in March 1945 in Stalag 7A. Fred worked in the kitchen as a cook. Stale bread, often with weevils and sawdust as filling, and weak soup where rationed to the prisoners by the Germans. The prisoners had to rely on food provided in Red Cross packages which were not always delivered on time, or at all, because of pilfering by the Germans.

|

|

Below is gunner Edward L. Dement's description of Stalag Luft III from his book "Sergeant, for you the War is Over" | |

"There were five compounds at Stalag Luft III. The British were in the North and East compounds, the Americans were in the West, Center and South compounds. The camp, about ninety miles southwest of Berlin, was approximately one-half mile south of the town of Sagan, which boasted a population of about 25,000 people in the province of Silesia." . . ."Apparently, the camp had not been located there by accident. The spot was well away from all combat zones and even further away from any friendly or neutral territory . . . Equally important, Sagan lay at the juncture of six rail lines. Bringing the prisoners to camp was therefore easier, but so were their escape attempts.". . . "The routine of life in Stalag Luft III began the moment the prisoners passed through the main gate into the vorlager . . . First the prisoners were counted and thoroughly searched, finger-printed, and photographed . . . Finally, the men were issued their bedding; two blankets, one sheet, one mattress cover that held the wood shavings for the mattress and served as bottom sheet, one pillow case, one pillow filled with straw, and one small face towel. Our clothing consisted of one overcoat, three pairs of socks, pair of wool trousers, three shirts, three pairs of winter underwear, one sweater, one pair of high shoes, a scarp, a pair of gloves, one belt or suspenders, a cap and four handkerchiefs. Since the Red Cross clothes were considered only a loan rather than a gift, the prisoners had to be reminded continually not to modify them . . . In addition, they were given a two-quart heavy mixing bowl, a cup, a knife, a fork, and a spoon. These items would not be replaced if broken. The men were then sent into one of the compounds." ". . . Center compound of Stalag Luft III consisted of 20 barracks, cook house, theater, shower building, laundry building and a fire pool . . . Each barracks had a central hallway with rooms on both sides. In addition to 13 rooms accommodating 12 to 16 men each, was a washroom, a tiny kitchen, and a latrine. Each cooking group was assigned a scheduled period, usually rotating on the communal stove." "Each night, German guards with their German Sheppard dogs would make the rounds at 10:00 pm, barricading the barracks doors with a wooden bar. No one was permitted out of the barracks at this time and another group of guards and dogs constantly patrolled the area to see that the rule was observed. Radios were not permitted in camp by the Germans, but BBC (British Broadcasting Company) news was carefully circulated amoung the men, attesting to the presence of concealed sets in the area. One set was being used and was concealed in a British cigarette carton, measuring four inches in length, three inches high and eleven-sixteenths of an inch in thickness . . . When available, the news was carried from barracks to barracks by a newsman whose arrival in a pre-arranged room was announced to the barracks by the call 'Soups On' ". " . . .The prisoners seemed to have recognized various stages of barbed-wire psychosis in themselves and others. The mildest forms consisted of nothing more than increasing inability to concentrate. The worst cases were actual insanity . . . Most prisoners had little difficulty recognizing the symtoms in someone else . . . If the blues were becoming a problem, getting out to cheer someone else up frequently helped, then it was easy to laugh." " . . . There were restrictions on the number of letters prisoners could receive from home. Many men waited six months to receive their first letter . . . I received my first letter on October 4, 1944." Note: Edward L. Dement was captured on April 3, 1944 |

Follow this link for a history of Stalag Luft III. |

As the end of the war neared, the Germans had to evacuate the camp due to the pressure from the advancing Russians. My father, Frederick G. Abner, Jr. and all other prisoners were forced to go on what has been called the “Death March” from Stalag Luft III to the prisoner camp in Moosburg, Stalag Luft VIIA. Because of the overcrowding at Moosburg, conditions in the camp were almost intolerable.

| |

"At 1500 hours on January 17, 1945 the Germans' news broadcast announced unprecedented Russian advances toward the camp . . . On January 22, 1945 General Vanaman ordered every compound commander to prepare the camp for possible evacuation . . . On January 27, 1945 at 8:30 am, as many men as possible crowded into the auditorium to hear what General Vanaman had to report. He told the group that one of three things was going to happen. The German guards will either evacuate or surrender the camp to the Russians. The Commandant will be ordered by some high fanatical official in Berlin to put us to death, in which event we must fight for our lives in hopes that some of us will be saved. Or, we will be evacuated on a long march across Germany. In that event, we will suffer many casualties. The Russians were only 22 miles away from the camp." " . . . On Saturday, January 28, 1945 in the early afternoon, the rumble of artillery could be heard approximately 15 to 20 miles away. At 9:30 pm, the order to evacuate the camp was announced. We were told to be ready to start marching in one hour . The Commandant had intended to surrender the camp but orders came from Berlin to evacuate Sagan immediatly and move the entire 10,000 prisoners in the direction of Berlin ." " . . . In spite of our best efforts, the prisoners had to leave a great deal behind . . . Estimates suggest that between 25,000 and 55,000 Red Cross parcels were left . . . Center compound fell out at 11:30 pm on January 28, 1945. Everyone was warned that all guards were heavily armed and had been ordered to shoot any man who breaks rank or who deliberately disobeyed orders. For every 60 men, there was one guard and one dog on each side of the column. The dogs were more effective than the guards . . . Approximately 500 prisoners were too sick to be moved and a few medical personnel, clergymen, and healthy prisoners also remained to help care for them."" . . . Snow had begun to fall several days before the march began and about six inches had accumulated by the time the men left the camp . . . many prisoners were able to build sleds upon which to carry their possessions . . . they proved to be a boon . . . The low temperatures were another matter. Estimates range from 10 degrees to 20 degrees below zero. Snow fell through the night and the wind created blizzard conditions at times. The harsh weather soon took its toll upon the weakened men and the columns began to stretch out as fatigued men fell farther and farther behind." " . . . While some prisoners witnessed isolated shootings, there were apparently few such instances. I, myself, did witness a shooting from a guard of one of my friends. The sergeant was in front of me and bent down to tie his shoe, whereupon the guard pulled out his pistol and shot him in the back of the head. No one was allowed to touch him and the guard pulled his body out of the formation and threw him into a snowbank." " . . . It was cold and snow was stacked two feet deep, and more snow continued to fall. German civilians cleared the center of the road as the formation passed by them through the town of Sagan. We watched in silence as soldiers of the German army and SS hurried the civilians into the endless line of marchers. German civilians who resisted were shot. The SS never argued. A rifle shot saved time and settled all arguemnts." " . . . It soon became clear that the Germans had made little or no provision for their care on the journey. A few wagonloads of bread were sent along with several of the columns, but the prisoners ate mostly the food that they carried on their backs. They bartered for some food along the way. Water was obtained by digging in the snow and letting it melt in your mouth . . . Shortly after 8:00 am, the Germans ordered a 15 minute rest . . . Just past 4:00 pm we entered the small town of Wharton and stopped for a break. General Vanaman refused to go further without an overnight stop. He and the Commandant had a furous argument. Gerneral Vanaman stood firm and the commandant finally ordered an overnight stop." " . . . we were assigned to a Roman Catholic church capable of seating 400 people. It took 1 hour and 40 minutes to pack 2,000 into the small church interior. The balance of the prisoners were left outside . . . there were no latrine facilities outside the small washroom. We had to use the cemetery by sitting on the tombstones. It must have been a terrible site after the snow melted in the spring . . ." After nine more days of marching and sleeping in crowded churches and barns . . ." . . .On Tuesday morning, February 7, 1945 . . . It was announced that several freight trains would take the prisoners from Spremberg to Stalag 7A and the trip would take three days and nights . . . Fifty men were marched to a boxcar for loading. Most of the cars had benn used for hauling cattle. The inside of the cattle cars were filthy. The smell was unbearable. There was no room for us to lie down, or even sit down . . . Four pasteboard boxes were placed in each of the four corners of the car to be used for toilets or sickness . . . We suffered most from thirst. Fnally, the toilet boxes overflowed." Thursday morning the train pulled into Regensburg. The doors opened and we were unloaded . . . There was a pond just ahead of the engine . . . We broke ranks en masse. Guards fired in the air. Nonetheless, we moved to the water, men drank and filled cans and jars . . . Late Thursday afternoon we arrived in Munich . . . At no time were we given food while on the train . . . After dark, the train pulled out of Munich. The following morning, we were unloaded on the north side of the city of Moosburg (Stalag 7A)." "It was Friday, February 10, 1945, 11:00 am. The march had come to an end We had travelled across a large part of Germany, a distance of 480 miles . . . Over 3,000 men were sick with infected stomachs, dysentery, colds, and pneumonia. We were all weak from malnutrition, mental and physical exhauston." |

|

|

Follow this link for more information of the Death March. |

General George S. Patton liberated Moosburg on April 29, 1945.

|

"A Colonel in the SS was present. At his insistance, the General declined the terms and decided to make a last-ditch effort to fight. The General was informed that Patton's Third Army was part of the American Seventh Army which would attack at 8:00 am on April 29,1945. Patton warned that if any one of us was harmed by the Germans, those Germans would be executed." "At 8:14 am large clouds of dust rolled over the hill about two miles away. As far as anyone could see, there were tanks looking down the hillside. Five squadrons of fighter planes were coming over our way. The siren sounded loud and clear over the entire camp. In a few minutes, we were locked in and all shutters were closed. Floor boards were quickly ripped from the floors. Men got under tables and beds. Some laid on the floor and I am sure all men were praying to get through our ordeal and that this was not the end of our lives." "Machine gun bullets began bursting in every direction, attacking the sentry towers. The roar of tanks got louder and the German guards started shooting machine guns. The roar of tanks, planes, and guns blasted against our eardrums. We heard the crashing and ripping of steel . . . Suddently, everything stopped, except the movement of tanks close by. Out of nowhere came a Piper Cub flying low over the camp and dipping his wings. We knew that the battle was over." "When I got out of the barracks, there were men climbing out of windows and climbing to the roof. There was an American tank going through the main gate. The battle had lasted not quite 20 minutes. The guards that were still in the camp surrendered to our officers. The prisoners rejoiced in their new freedom."

" . . . Somewhat later, General Patton arrived in his command car. It was not the dull green usually seen at the front, but brightly shined and suitably decorated with sirens, spotlights, and a four-star flag. He toured a few buildings . . .

. . . and then mounted the hood of his car to speak. As usual, Patton was immaculately dressed in whipcord trousers, boots, battle jacket, two ivory handled pistols, and a helmet polished to a high sheen. Patton was a very imposing figure with a harsh face. He stood rigidly at attention; a man more than six feet tall, weighing approximately 200 pounds. The General grabbed the microphone attached to the loudspeaker on his car and addressed the crowd in a high-pitched, almost falsetto voice." "After holding up his hand for silence, General Patton looked up and saw a Nazi flag still flying. Pointing toward it, he said, 'I want that son-of-a-bitch cut down and the man who cuts it down, I want him to wipe his ass with it.' Then he said, 'Well, I guess all you sons-a-bitches are gald to see me.' Immediately a great roar went up. After the noise calmed down, Patton continued, 'I'd like to stay with you awhile, but I have a date with a woman in Munich. It is 40 kilometers away and I've got to fight every damned inch of the way. God Bless you and thank you for what you have done.' Within seconds, he stepped back into his car and drove away." Within an hour, three truckloads of women nurses and American Red Cross workers arrived. They handed out gum, cigarettes, doughnuts, and coffee. White bread was also issued and tasted like cake. A sound truck with a loudspeaker started playing records. The first American song we heard was 'Don't Fence Me In'." From Ed Dement's book, Sergeant, for you the War is Over. |

Over the next few weeks, all the former American prisoners of war were transported to Le Havre, France to Camp Lucky Strike to await transport back to New York City in liberty ships. Fred Abner departed France on May 23, 1945 and arrived in New York June 3, 1945. Ed Dement arrived in New York Harbor on June 10, 1945:

|

|

|

| Honorable Discharge Certificate |

| Report of Separation and Honorable Discharge |

|

|

|

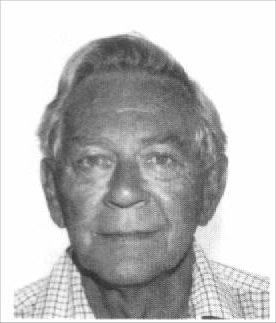

Frederick G. Abner, Jr. went back to his job at Walter C. Davis and Sons, Inc. in Alexandria, Virginia after getting home from the war. He worked there as an electrician and electrical foreman on many large construction projects in Alexandria and the surrounding Washington, D.C. metropolitan area for the next 45 years. He met and subsequently married in April of 1946 Frances A. Albright, a wartime employee of the Bell Telephone and peacetime librarian at the Library of Congress.. Mr. and Mrs. Abner had three children, two boys and one girl, over the next 8 years and settled in the small community of Groveton, Virginia. | Frederick G. Abner, Jr. died on April 27, 1992. He was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetary. |

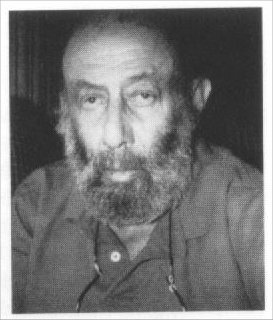

George L. Dancisak married Ethel his wife of 41 years, shortly after his return to the United States. After the war, George spent 23 years working for the Standard Oil Corporation and 17 years as Deputy Assessor in the North Township Assessor's Office in Lake County, Indiana. George was an active grassroots environmental educator and wildlife conservationist. He dedicated much of his life to improving the air and water quality so that future generations could enjoy fishing and hunting in northern Indiana. For his efforts he received several awards the most notable being Outstanding Conservationist of the Year in 1978. It culminated a lifetime of loyalty & devotion to conservation in Indiana and recognized his concern for education, and preservation of natural resources. Along with his wife, George raised 2 daughters and 2 sons. |

| George L. Dancisak died while “serving a short tour in the Veterans Hospital” on February 11, 1986. |

Edward L. Dement lives in Florida and was married for 52 years. He is the Vice Commander of the Florida POW Association. | Ed is an active member of the 456th Bomb Group Association. |

|

Milton H. Halberstadt was discharged on Jan. 28, 1945 with the rank of 2nd Lieutenant. He received the Purple Heart, Air Medal, and Distinguished Flying Cross. He and His wife had three sons. |

| Milton H. Halberstadt passed away in the year 2000. |

|

When Howard N. Hartman arrived home by train, Lt. Emil (Jeff) S. Laszewski surprized him by being on the platform. Howard graduated from Ohio State University after the war. He married Martha Cox in 1950. They had three children. Howard retired in 1987 and passed away in 2008. Howard and Martha are buried in Arlington National Cemetery. |

| Howard served as Vice President and President of the 456th Bomb Group Association. |

|

I would like to thank the following for their help in compiling this record. Robert W. (Bob) Reichard, my first contact with the 456th Bomb Group Association, Howard N. Hartman, the co-pilot of my father’s crew, Edward L. Dement, top and nose turret gunner, and Michael J. Dancisak, Ph.D at Tulane University and son of my father’s friend and crew mate in the Army Air Force, George L. Dancisak, Hans Halberstadt of Military Stock Photography and son of Milton L. Halberstadt, and of course the 456th Bomb Group Association for maintaining and preserving the history of the bomb group at their web site 456 Bomb Group. In addition to the web site, the 456th Bomb Group Association published in 1994, the history of the group during the war in the book 456th Bomb Group 1943 – Steed’s Flying Colts – 1945 by Fred H. Riley, the association’s historian, printed by Turner Publishing Company, Paducah, Kentucky. Lastly, I would like to thank theUSAF Academy Libraries for their information on Stalag Luft III. |

| Select to Contact Us |